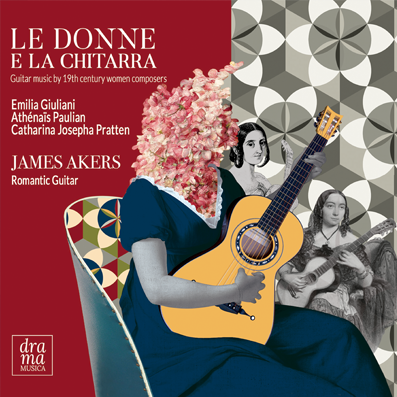

LE DONNE E LA CHITARRA

Guitar Music by 19th Century Women Composers

James Akers - Romantic Guitars

DRAMA004

Release Date: 15th November 2018

Le Donne e La Chitarra

Music for guitar by 19th century women composers

“I had to rescue the guitar twice, firstly from the noisy hands of the flamenco players and second from the poor repertoire that it had.” Andrés Segovia

“What is history but a fable agreed upon?” Napoleon Bonaparte

The figure of Andrés Segovia looms large over the modern history of the classical guitar. A musician of international renown, a forceful personality and charismatic performer, he is credited with single-handedly forging an auto-didactic path that lead to the acceptance of the guitar in the classical music world. Throughout his long career Segovia told, re-told and refined the story of his life and struggle to impart his vision to the world. By the time he died, in 1987 at the age of ninety four, he had been feted and ennobled, given over five thousand recitals, created a considerable discography and written a partial autobiography.

In Segovia’s narrative, his own work and career are uniquely significant to the history of the guitar. He allows for few colleagues or contemporaries but has the capacity to embrace numerous devoted disciples. Being a proud Spaniard, the country of his birth became the home of the guitar and the works of its nationalistic composers, the core repertoire. Because of Segovia’s exceptional achievement, fame and strength of character, few questioned this narrative. It became the prevailing mythos of the classical guitar, emotionally invested in by aficionados, revived and repeated in newspaper articles, books, television documentaries and radio programmes, swallowed whole and regurgitated by a willing audience, in thrall to the simple rags-to-riches tale of individual genius and indomitable will.

Segovia’s story conveniently fits into the great men mode of traditional narrative history, creating a clear causal progression of events through time, dominated by powerful individuals. Akin to the conventions of fiction, this method of interpreting the past avoids the emotional discomfort of confronting the complex reality that underlies human experience, with its unpredictable events and chance encounters, and credits all outcomes to human agency.

To reflect on humanity’s preference for clear linear narratives is not to cast aspersions on Segovia himself, whose vision and artistry communicated to millions, but is to observe the unfortunate outcome an oversimplified view of history can have on those left behind. As a consequence of the general acceptance of this story, many composers and performers, who existed outwith the mainstream narrative, have been neglected and their work relegated to obscurity. Central European composers including Ivan Padewicz (1800-1873), Adam Darr (1811-1866) and Johann Decker-Sheck (1836-1899) are barely known to this day; while it is only since Segovia’s death that Johann Kaspar Mertz’s (1806-1856) music has become widely performed. The compositions of the eccentric Bolivian, Augustin Barrios Mangoré (1885-1944), now revered, are thought to have suffered initial neglect due to Segovia’s lukewarm endorsement of their author; while a manuscript copy of the Etudes by the great Giulio Regondi (1822-1872), who had a close association with one of the composers featured on this recording, having been gifted to Segovia during a tour of Russia, languished unheeded in his library, only becoming an essential addition to the virtuoso literature after the Maestro’s death.

If the conventional historical narrative of the guitar caused the neglect of a great deal of music, the composers featured on this recording suffered the added adversity of being women in a male dominated world. They were overlooked by history, occasionally referenced, footnoted as anomalies but rarely championed or performed. However, to say these women lived lives devoid of appreciation is to do an injustice to their times. Madame Sidney Pratten (1821-1895) toured Europe as a child prodigy, was well known in English society and was the subject of a glowing biography. Athénaïs Paulian (1802-c.1875) was a friend of many of the leading guitarists of the day and dedicatee of numerous works; while Emilia Giuliani (1813-1850) shared the stage with Franz Liszt and was judged his equal by audience and critics alike. The neglect of their work can’t be blamed solely on misogyny but is also due to the human weakness for simplistic historical narratives that leave out inconvenient exceptions.

Little can be confirmed about the life of Athénaïs Paulian. She was born in Alsace in 1802, married in 1837 and died in the mid-1870s. This paucity of biographical information contrasts with the obvious impact she had on her contemporaries, many of whom were inspired to dedicate works to her. These included, Antoine de L’hoyer, Dionisio Aguado and Fernando Sor. Paulian published only one work, a collection of four themes with variations, based on melodies popularised by Angelica Catalini (1780-1849), a famed singer of the early 19th century, renowned for her virtuosic ability to sing highly decorated melodic lines.

Paulian’s first set of variations is based on a melody from Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Das Klinget so herrlich. It begins with a simple arrangement of the melody, followed by well-crafted tuneful variations that maintain the diatonic harmonies of the original theme while exploring the full range of the instrument. To the Mozart variations, Paulian adds a short concluding coda, a little left-over energy following the climactic final flourish.

The remaining two sets of variations by Paulian, on this recording, adapt popular songs of Italian origin, Margin d’un Rio and La Biondina. Neither melodycan be easily attributed to an individual composer as they appear in numerous settings, including a cantata by Alessandro Scarlatti and in an arrangement by Beethoven. Paulian’s versions are charming and effective. While well written for the guitar and displaying a pleasing melodic sense they possess no visionary originality or harmonic ingenuity yet, within their aesthetic confines they are highly successful pieces and reward repeated listening.

Frequently, family connections enabled women composers to access a high level of musical education, cultivate the contacts required to pursue a career and, thereby, overcome some of the prejudices against their sex. The names alone of Francesca Caccini, Barbara Strozzi, Fanny Mendelssohn, Lilli Boulanger and Imogen Holst attest to their links to prominent artistic families. In this regard, the classical guitar is no exception, with both Emilia Giuliani and Madame Pratten being endowed with impeccable familial credentials. Emilia Giuliani was the daughter of the celebrated Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829), whose compositions and performances had a similar impact in their day to Segovia’s in the 20th century. Sadly for Emilia, by the time she launched her own career, interest in the guitar had wained and she struggled to emulate the success of her father. She travelled widely throughout Central and Southern Europe, making a considerable impression on those who heard her perform, but was never able to attract a large following or a substantial market for her compositions. She died in Budapest of a ‘putrid fever,’ leaving behind a few scattered pieces, ever in the shadow of her famous forbear.

As a composer, Emilia Giuliani’s work only superficially resembles her father’s. Even in his most extended and adventurous pieces Mauro, ever the craftsman, stays within the harmonic and formal boundaries of Viennese classicism. Emilia, however, explores the outer reaches of her singular harmonic imagination with a fresh and daring disrespect for convention. Her Sei Preludi op.46 are a unique contribution to the classical guitar repertoire. While much guitar music inhabits a world of measured charm, endeavouring to delight rather than agitate the listener’s senses, Emilia demands immediate and complete attention. Her abrupt modulations to distant keys, chromaticism and adventurous use of dissonance are highly individual additions to the sound world of the romantic guitar. These characteristics are notably evident in the Sei Preludi in which Emilia takes specific ideas- a melody, arpeggio or technique- and develops them in thrillingly inventive ways.

In addition to the preludes, ten other pieces by Emilia have survived: six Belliniani; arrangements of excerpts from operas by Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835), mimicking Mauro’s similar treatment of Rossini in his celebrated Rossiniane, and four sets of variations, based on themes from popular Italian operas. The third of the Belliniani is presented on this recording, featuring material from the operas La Straniera, Beatrice Di Tenda and La Sonnambula, beautifully arranged for guitar, to allow Bellini’s famed melodic gift to be expressed in a small setting; along with Emilia’s Variazioni sopra il teme “non più mesta accanto al Foco” from Rossini’s La Cenerentola, an attractive piece that mines significant depths from its slight source material.

Madame Sidney Pratten was born Catharina Josepha Pelzer in Mulheim in Germany, the daughter of Ferdinand Pelzer (1801-1860), a respected guitarist, composer and teacher. By 1829 the family had re-located to England with Ferdinand, taking advantage of the popularity of the guitar at that time, establishing himself as a teacher and joint publisher of the world’s first guitar magazine, the Giulianiad. Catharina began learning to play the guitar in early childhood and by the age of seven had achieved sufficient mastery to begin giving public concerts. She toured throughout Europe, with the equally prodigious Giulio Regondi, to considerable acclaim. A critic wrote of her London debut, “her touch is powerful and her execution wonderful…we were surprised how such tiny fingers could draw forth such perfect sounds.” Upon reaching adulthood, Catharina was encouraged by a patron to settle in London and established herself as a guitar teacher. In 1854 she married the eminent flautist and composer Robert Sidney Pratten (1824-1868). Thereafter, she became Madam Sidney Pratten, the name under which her compositions were published. After her husband’s death, she remained in London, teaching, composing and performing. Surrounded by a devoted clan of patrons, pupils and admirers, including a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, she played host to visiting luminaries of the guitar world, including Francesco Tarrega, and stayed abreast of the evolving music scene around her.

Catharina Pratten was a prolific composer of guitar music. A substantial proportion of her output is didactic in purpose and was included in the three guitar methods she published. One of these publications gives instructions in how to play a guitar with the strings tuned to a chord of E major. This scordatura, allowed Pratten to create unique sonorities and effects in some of her pieces, especially in her Fantasia on Malbrook. In this delightful work, the warmth of sound and breadth of tonal possibilities created by the sympathetically resonating strings is brilliantly exploited. Pratten’s imaginative use of harmonics is especially effective and adds to the beautifully paced build-up of the piece toward its arpeggiated conclusion.

Amongst the studies in Pratten’s first guitar method is a stately hymn-like composition entitled Marche Funebre. Taking this piece as a foundation, on this recording, a collection of three of Pratten’s studies, of similar mood, have been combined to create a Rhapsody Funebre, allowing these short pieces to be heard within a bigger structure.

The Carnival of Venice is a seemingly unlikely melody composers have often used as a foundation for writing variations. From Chopin and Paganini to Tarrega and Mertz this simple tune has brought out the most technically demanding tendencies of these virtuoso composer performers. Patten’s variations are a worthy addition to this tradition, highlighting her mastery of the instrument and its range of tone colours and techniques. Elfin’s Revels, however, expresses a very different aesthetic. A prime slice of Victoriana, this whimsical product of a less cynical age partakes of the 19th century’s interest in magical creatures, to tell a simple tale through words and music. Though slight in content, both literary and musical, the effect is greater than the sum of its parts and speaks clearly of its creator’s connection to the cultural world around her.

© JAMES AKERS, London 2018