Sor and Giuliani and the first Golden Age of the Guitar

Throughout their history, plucked string instruments have been used to accompany the voice. From the kithara and lyre of the ancient world to the modern electric guitar the practical convenience and expressive potential of this combination has been exploited to great effect by performers and composers. The relatively recent invention of music notation allows us only a glimpse into this enduring history. The earliest surviving examples date from the 16th century, in which the already sophisticated and evolved nature of the music clearly demonstrates it was built upon a long tradition, and not newly sprung from a fecund imagination.

There are numerous examples which illustrate the success of this pairing. In the mid-16th century Luis de Milán (c.1560-c.1561) published songs for vihuela da mano and voice. The refined elegance of Pierre Guedron’s (c.1570-c.1620) Air de Cour for voice and lute existed contemporaneously with the great melancholy outpouring of English lute songs by John Dowland (1563-1623); while in Italy Giulio Caccini (1551-1618) described the lute’s descendant, the theorbo, as the finest instrument for accompanying the voice.

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, plucked instruments were integral to European music making, as they have continued to be in the Asian and African traditions to the present day. By the 18th century, however, advances in keyboard instrument building meant the harpsichord began to take over this pivotal role. The lute and theorbo gradually fell out of use while the guitar continued its evolution on the fringes of musical life. With the invention of the piano-forte, the first keyboard instrument to be able to imitate the changes in volume capable on a plucked instrument, the ascendancy of the keyboard was complete and a new tradition of song came to the fore.

The guitar, though sidelined, continued to be played and attracted a loyal and devoted clique of practitioners and aficionados devoted to keeping the flame alive. However, during the age of the first peak of piano accompanied song, with the inspired lieder of Franz Schubert, the guitar achieved a degree of popularity not seen since the 17th century. Driven by the appearance in Europe’s capitals of virtuoso composer performers, who captivated and inspired their audiences, this “golden age” of the guitar also produced a new repertoire of song. These songs, however, were often also published with alternative accompaniments for the piano, to ensure maximum sales potential - an aknowledgement of the dominance of the keyboard.

Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829) is a seminal figure in the history of the guitar. Born in southern Italy he settled and passed much of his professional life in Vienna. He interacted with many of the leading musical figures of his day, including Beethoven, Rossini and Paganini and his fame spread throughout Europe, to the extent that an English guitar magazine was named after him, The Giulianiad. Giuliani composed in a variety of genres from concertos with orchestra to solo chamber pieces but the guitar is always central to his music. A large proportion of Giuliani’s output is in the form of vocal composition. He wrote not only original pieces but made a large number of transcriptions of well-known vocal pieces by, amongst others, Domenico Cimarosa (1749 - 1801), Felice Blangini (1781 - 1841), Gioachino Rossini (1792 - 1868).

Giuliani’s own songs are among his finest works. Setting aside his abilities as a guitarist, Giuliani concentrates on the vocal line, creating dramatic word setting, supple and inventive melodies and swift changes of mood. Written in the Italian operatic style Giuliani imbibed in his youth, each of the Ariette takes the listener on an emotional journey perfectly expressed in crystalline miniature. A characteristic of Giuliani’s music that is often discussed is his melodic gift. His ability to imbue the potentially dry sound of the guitar with a cantabile warmth, while employing various techniques to explore the expressive depths of the instrument. This is remarkable considering the nature of the guitar in the early nineteenth century. The instrument of Giuliani’s day was smaller than a modern classical guitar, the treble strings would have been made of gut, dried sheep intestines, which have a unique timbre and give less projection than modern strings. To achieve the range of expression attributed to Giuliani from such unlikely foundations is a testament to his genius.

The pieces performed on this recording highlight Giuliani’s versatility, imagination and mastery of style. His Sei Ariette, op. 95, were inspired by the music of his contemporary, Rossini, a monumental figure in the history of Italian opera. They were published by Artaria & Co. in late 1818, shortly before Giuliani’s final return to Italy. Arietta literately means ‘little aria’, a less complex form than a standard aria, characterised by its brevity, variety of ornamentation and generally upbeat mood. According to the first published edition, Sei Ariette was ‘humbly composed and dedicated to Imperial Highness Princess Marie Louise, Archduchess of Austria’, revealing the work’s significance and the affection and respect that Giuliani held for his benefactress. The set is comprised of the following songs: I. Ombre Amene (Andantino espressivo). II. Fra tutte le pene (Allegretto agitato); III. Quando sarà quell dì (Allegretto); IV. Le dimore amor non ama (Maestoso); V. Ad altro Laccio (Allegretto), and VI. Di due bell’anime (Allegretto). The Ariettas demonstrate a wide range of character, from the very sweet Ombre amene, to the contemplative Quando sarà quell dì, the imposing Le dimore amor non ama to the energetic and sparkling Fra tuttle le pene, Ad altro laccio and Di due bell’anime.

Giuliani’s Grand Overture is one of the core pieces of the guitar repertoire. Written in the style of an opera overture, it begins with a slow opening section full of gravitas, with occasional stabs of impending menace, before charging off on a dramatic gallop around the fretboard of the guitar, and enjoying a suitably extravagant ending. In this programme of song it has the function of its original inspirational, as an overture to the Cavatine that follow.

The Sei Cavatine Op. 39 were published in 1813 in Vienna, also by Artaari & Co., and dedicated to ‘Sig. Conte Francesco de Pálffy’, one of Giuliani’s most illustrious followers. This collection is printed with both guitar and piano accompaniments, which, interestingly, contain considerable discrepancies. The piano versions seem to be more considered and carefully composed than the slightly perfunctory efforts for guitar. Perhaps, on this occasion, the opportunity to compose away from the guitar exercised Giuliani’s imagination more than the ‘day job’ of writing for the guitar. Due to this inconsistency in the accompaniments, on this recording, some judicious borrowing from the piano versions has been used to enliven the guitar parts. In the Sei Cavatine, Giuliani creates clear and bright melodies over simple harmonic foundations demonstrating admirable invention with beautiful results. It consists of six settings of Italian love poems by unknown or anonymous authors. The titles are: I.Par che di giubilo (Allegro maestoso); II. Confuso, smarrito (Allegro); III. Alle mie tante lagrime (Moderato); IV. Ah! Non dir che non t’adoro (Allegretto); V. Ch’io senta amor per femine (Allegro vivace) and VI. Già presso al termine (Allegretto). The second piece is perhaps an adaptation by Guliani of the cavatina Confusa, smarrita from the opera seria Catón en Útica (1728) by Leonardo Vinci (1690-1730). This popular text, by poet Pietro Metastasio, appears in over thirty settings by various composers.

From a singer’s perspective, it is liberating to be able to enjoy the beautiful ‘bel canto’ lines and poetic texts without having to compete with the sound of a whole orchestra. Both Ariette and Cavatine provide considerable opportunity for expression and being accompanied by the delicate sound of the guitar allows the creation of operatic drama within a chamber music setting.

Fernando Sor (1778-1839) was a prolific composer of song. Though most famous as a composer for guitar, considered the finest of his day, he was less wedded to the instrument than Giuliani. He composed widely in other genres including opera, ballet and piano music. Most of Sor’s songs are composed with piano accompaniment and he had considerable success as a songwriter while living in London. His Seguidillas are among the few songs he composed with accompaniment for guitar. Based musically on the bolero dance form they are short pieces with simple often bawdy and euphemistic texts outlining some of the less courteous interactions between the sexes. The seguidilla lyric is a poem of seven lines, the first four of which are the ‘copla’ or verse, the next three the

‘estribillo’ or chorus.

Sor’s studies have been central to the aspirant guitarist’s experience for nearly two centuries. Study 17 op. 29 achieved fame in the mid-twentieth century when it was chosen by Andres Segovia as one of the collection of twenty Sor studies he edited and published. This collection was recorded by leading performers including Narcisco Yepes and John Williams. The piece deserves its popularity. It is a beautifully structured contrapuntal fantasia, beginning with a joyously lilting melody, which sets the scene for a good-natured but deceptively complex work, sounding effortless and light but rich with compositional learning and facility. The Meditación is a less well-known piece. Dedicated to Trinidad Huerta (1804- 1875), another celebrated guitarist and composer of the 19th century, who history has chosen to neglect, it inhabits a nocturnal world of melancholic contemplation, not unlike the depths of feeling ploughed by Sor’s equally celebrated predecessor in the world of plucked string composition, John Dowland. On this recording, in keeping with the performance practice of Sor’s day, an original cadenza is added after a marked pause with the intention of heightening the emotional impact of the piece.

The Six Seguidillas presented in this recording illustrate perfectly the symbiosis of the popular and the refined. A parallel can be drawn between Sor’ seguidillas and the paintings of Francisco de Goya’s first period - those that portray the games and amusements of ordinary people while giving them an aristocratic bearing. In the Seguidillas, Sor employs melodies, which could have been heard with various lyrics in Spain at the beginning of the 19th century. Due to his refined composition technique Sor is able to present them with a sophisticated veneer while preserving the rhythmic energy of the most famous dance of the age. The temperament of each song chanes according to the text ranging from the passionate Cesa de atormentarme, the joyful De amor en las prisiones, romantic and dreamy Si dices que mis ojos and Mis descuidados ojos, the prudent El que quisiera amando to the very witty and ironic Las mujeres y cuerdas.

Sor, in his songs, challenges the singer with his demanding melodies, containing fast runs, trills and ornaments. These add to the character of the songs which, combined with the amusing lyrics, inspire the performer to search for an inner ‘Spanish’ soul. Compared with Giuliani’s songs, which allow for rubato - freedom with the timing - in different sections, it is necessary to respect in Sor’s work the characteristics of the dance form that are the foundation of the seguidilla. Thus, the singer must let the music move and not interrupt its flow with too many long breathes!

With the passing of Sor and Giuliani, the guitar returned to its position as a niche instrument for amateurs and eccentrics. Notable figures followed but none achieved the celebrity of their predecessors until popular culture adopted the guitar as its lynchpin and a new journey began.

We would like to dedicate this album to Brian Jeffery in recognition of his unparalleled contribution to the historical guitar repertoire. By discovering and making

accessible, through Tecla Editions, sources of music long forgotten he has greatly enriched the experience of performers and audiences for generations to come.

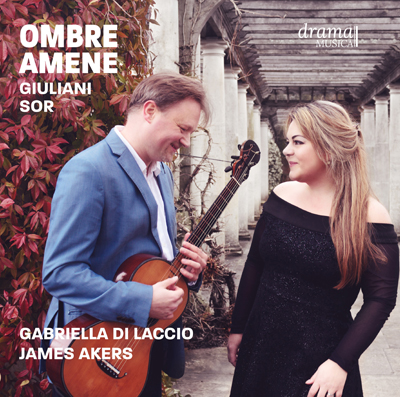

Gabriella Di Laccio & James Akers